A vividly woven life story

Having been born in 1950 in postwar Lendava meant for Marika Danč that she began her life among remnants of an ancient and rich bourgeois era and was, at the same time, on the threshold of fresh prospects promised by a new land of new people. Her family, consisting of father, Viljem, a private tailor, mother, Marija, and two years younger brother, Viljem, lived by old world standards. Educated in Budapest, Zagreb and Vienna, the sartor of tailcoats and other more demanding products earned a decent living for his family; in time they bought a house and lived on the first floor of one of the old town’s most imposing buildings that once housed the overseer of the (Eszterházy) Count’s estates and later served as the forestry administration headquarters.

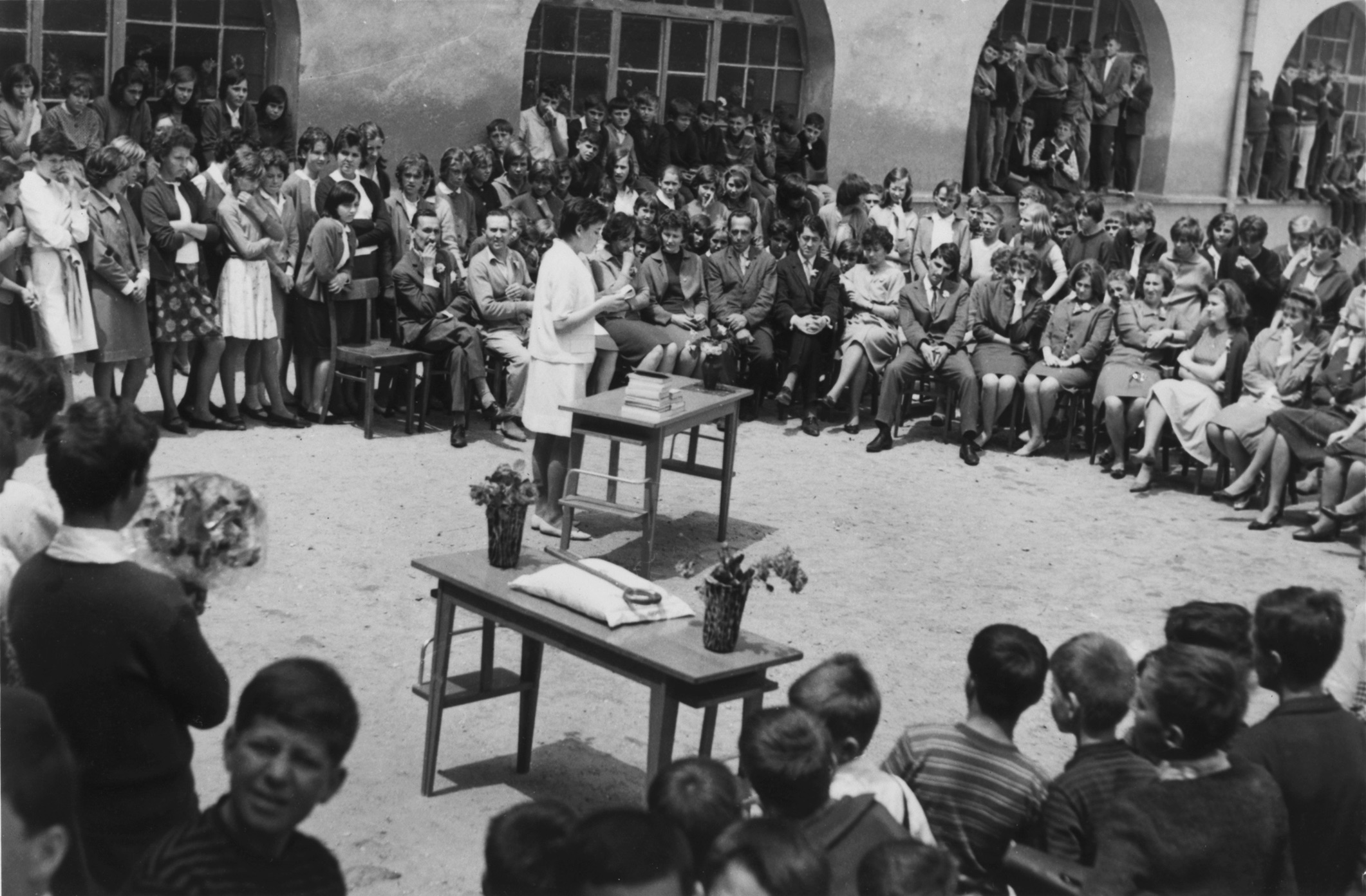

Marika attended primary school in Lendava’s castle; she was recognized by teachers and classmates alike for her fondness of drawing. She enjoyed piano lessons in the newly established music school and was mournful when financial difficulties forced her mother to sell their piano. Marika only vaguely recalls her father’s successful tailor shop with its apprentices and customers. Her father died in 1964 after many years of illness and operations. At a time when society did not support private trades, the family received neither the income nor the benefits that, in principal, children and families should have been entitled to under such circumstances, so her mother soon took a job in the growing INDIP company. Even though her emotions were divided after her father’s death, the unenviable situation of her family did not diminish Marika’s unwavering determination to go to an art-oriented high school.

Youthful energy and great enthusiasm convinced her that she would succeed. Finding strength in her unfailing desire for life, she felt destined to take a big step into the unknown. The Zagreb Secondary School of Applied Arts was considered the best in the former country [t/n: Yugoslavia], but she was dubious about making it through the entrance exams because of the language.

Her bravery at the age of 14 in traveling alone for the first time to Ljubljana and then to Zagreb and staying for week-long, multi-faceted entrance exams in each city, foresaw the subsequent decisive steps that always reinforced Marika’s devotion to her initial calling – or to whatever calling she undertook — which she pursued with spontaneity, authority and resolution.

Zagreb, the traditional destination for a higher education, had shaped many of Lendava’s prospective students. Only a chosen few studied in those days, owing not only to talent, knowledge and ability, but also to personality traits. Competence (today we would say emotional intelligence) and a sense of responsibility, along with mental ability and diligence, led to the logical decision to study.

Most students in the 1950s and 60s with the slightest desire (and opportunity) for an education had to even attend high school away from home. Those from Lendava predominantly chose between Murska Sobota and Čakovec, although the high school in Varaždin was considered high quality on a wider national scale; still, Zagreb was selected for specialized fields, especially art. Quite a few young people opted for the linguistically closer Vojvodine, where they could continue their education in Hungarian.

Studying away from home meant expenditure for the family (scholarships were scarce), but whether to study or not was based predominantly upon the parents’ awareness of what an education contributed to life, regardless of initial sacrifices and often misfortune as well. All the same, it was a time when a professional education of quality, and to a great extent, a degree, meant social and intellectual leaps into a way of life completely different from that of the previous generation, for the country was making an unimaginable exponential growth, reaching its peak in the 1970s.

When Marika began attending high school in Zagreb in 1965, she lived with relatives and later, through their intervention, with a woman who looked after her strictly and consistently. During her last two school years, she resided with a classmate’s family, who took her under their wings after she had helped their daughter with art objects. She also worked wherever the occasion arose. Overcoming the not-quite-ideal conditions in the 1960s was similar for most students who went away to school. Characters were formed and work habits consolidated, resulting in anticipation and courage. Nothing was (too) difficult because the awareness that their path could only go upward was encouraging. Marika found language barriers surprisingly negligible. After a month of absorption, she quickly embraced Croatian, and it remains one of the many languages in which she fluently speaks, thinks and communicates.

Exuberant and fascinated by the chance to visit galleries, museums and the theater, the big city satiated Marika’s intellectual and aesthetic appetite. This atmosphere, hitherto foreign to her, was abundantly fulfilling and overwhelming. She formed professional and lasting bonds to which she has remained faithful in one way or another. Once a person becomes infected with the world of theater and art, it becomes a lifelong commitment.

After the first year of the five-year-high school program, and in spite of her initial decision to study painting, Marika selected textile from the numerous art and design majors, and her training in several directions drew her to tapestry, although she was also interested in fashion and textile design. Those early years in the city, surrounded by creative classmates and inspiring professors, confirmed that she had chosen the only conceivable path.

As chance would have it, Jagoda Buić, doyenne of Yugoslavian as well as of world tapestry, visited the student exhibition in Marika’s final high school year. She immediately invited Marika to work with her. They say no coincidences exist – at least that is what we call events that appear to happen in an appropriate order. Both the meeting with her future mentor and the theme of her exhibited tapestry were meaningful and formed life-long connections. Marika’s Willow theme was an association with home, origins, nature, the elemental. The desire to live somewhere else and in another manner does not preclude an attachment to where and whatever you came from. Marika has demonstrated this every step of the way.

The intellectual and emotional breadth of Zagreb left its mark on her. With its atmosphere and institutions, the former country’s most cosmopolitan metropolis significantly influenced the young artist’s views, values and professional and aesthetic parameters. And Zagreb generously welcomed the talented, capable crafts(wo)man and artist with open arms. Marika embraced knowledge and cooperation in perhaps the most creative, overt and, it might even be said, carefree period of a country that has left its cultural impact on all of us. Her intensively productive co-activity in assorted projects began immediately after she finished high school, i.e., even while she attended art classes at the Pedagogical Academy and studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts, she was working independently and passionately.

While studying at the Pedagogical Academy, Marika began to work unstintingly as assistant and collaborator with Jagoda Buić, whose mentorship — not only in a professional sense — was a major determinant in Marika’s career. After graduating in 1972, she worked for a few years as Jagoda Buić’s full-fledged assistant, which meant traveling and prolonged stays in Paris, Lausanne, Dubrovnik, Split, and of course, Zagreb.

Concentrated diligence and zeal were crucial for managing and guiding weavers and coordinating preparatory processes, dyeing, weaving, fashioning, followed by logistics to presentation sites and working with actors, singers, set designers and directors. After creativity, realization and many weeks of physically demanding work came sewing, measuring and completing costumes at performance sites. While assisting Jagoda Buić with costume designs, Marika gained invaluable experience and made acquaintances in key theaters, opera houses and festivals.

From 1970 on, Marika was a constant presence at the Croatian National Theater (CNT) in Split, working for the theater, the opera, the ballet. In her first years with Jagoda Buić, Marika took over and completed costume designs in 1973 for Inga Kostinčar’s role as Aida; at that time, the cult-like Hamlet was performed at the Dubrovnik Summer Festival (1974), directed by Dino Radojević, with Rade Šerbedžija as Hamlet. Simultaneously, independent requests began to come her way. Her consummate ingenuity, diligence, consistency and reliability were clearly evident, and she received special acclaim in Split for Orpheus and Eurydice, the first opera for which she designed the costumes herself.

Notwithstanding a general stereotype of disorganized artists, characteristic, but also cultivated qualities, intensified by life’s experiences, are necessary in the creative world, and, in truth, they are quite common. Marika’s approach to work and creativity was based on prodigious studiousness and consistent attention to all stages of preparation, craftsmanship and the coordination of participants in a process — whether in costumology for the theater and television or in other artistic endeavors. The process of creating was followed by production, dyeing, tailoring, cooperating with seamstresses, measuring, finishes, and adaptation to the creative team’s additional efforts, and Marika, with her outstanding originality, was seen as a very reliable and compatible element.

She received many offers for independent commissions, especially in Zagreb and at festivals in Split, Osijek, Dubrovnik and Pula. Reviews were exceptional, audiences enthusiastic, media comments filled with praise. During this period, Marika was involved in many coinciding projects. Alongside her first major theatrical costume assignments, she made her own tapestries, exhibited in solo and group exhibitions, took on teaching jobs and continued to work intensively with Jagoda Buić.

Despite the exciting appeal of such a life, at the initiative of older colleagues, artists, professors, and especially the sculptor and professor at the academy, Branko Ružić, she decided to continue her studies at the Academy of Fine Arts, which was her original wish after high school. She recognized the fact that, because of the work she took on to survive, but primarily due to the possibilities offered in the setting of Jagoda Buić’s mentorship, she had only gone in the direction of art pedagogy, and she had gained invaluable experience for a few years. In 1975, she enrolled in the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb and majored in painting.

After her first year, Marika chose Professor Ljubo Ivančić’s class, but the professorship changed when he departed due to illness, so she spent two years in the class of Professor Nikola Reiser, from where she graduated. Their mutual respect grew into a genuine, lifelong friendship and many joint ventures, just as it did with several other professors, most notably, Mladen Veža. Her connection with director, lecturer and translator, Vlado Habunek, was equally important. Owing to his gallant old school style, intellect, polyhistoric knowledge of the Croatian theatrical scene and mild character, the two kindred spirits developed a special friendship and support.

At the point where most artists are barely entering the field of artistic search and study, Marika was fully involved in creative production and social interactions in prominent cultural circles. The year she enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts, the architect and designer, Bernardo Bernardi — former president of the Croatian Association of Fine Artists of Applied Arts (ULUPUH) — opened her first solo exhibition at the Mali lapidarij gallery in Zagreb. Throughout her studies, she actively created, participated in costume design for theaters and television, and independently worked on many projects and commissions. Among her main and most notable enterprises of that time, employed as a freelance costume designer, were her first engagements: for the ballet, Orpheus and Eurydice at the CNT Split in 1973 (choreographed by Miljenko Vikić, once soloist at the CNT Zagreb); the presentation, Good Morning, Thieves, at the Jazavac Theater in Zagreb; the opera, Troubadour (directed by Vlado Habunek, with scenography by Boško Rašica and conducted by Nikša Barez); the Nikola Šubić Zrinski opera (choreographed by Mirko Šparenblek and directed by Vlado Štefančič) at the Pula Arena in 1976 and 1977 – these were among her most prolific years; Dido and Aeneas at the CNT Split (for which she received the Best Costume Design of the Year Award); Ariadne on Naxos at the CNT Zagreb, where critics wrote that the show was a feast for the eyes; the Barber of Seville in the Pula Arena, and The Power of Virtue at the CNT Zagreb.

Among Marika’s more interesting collaborations were the Gubec-Beg Rock Opera premiere, performed at the Zagreb Comedy Theater – where her macramé pieces gave rise to a working relationship with the legendary costume designer, Iko Košmrlj; and the Zagreb Histrion theater’s performance of Domagojada. Until her graduation in 1980, she contributed to many excellent and decisive theatrical productions such as Tosca and La Boheme at the CNT Osijek; Invitation to a Castle at the CNT Dubrovnik; Simon Boccanegra at the CNT Split, proclaimed the best opera performance of the 1978 season in Croatia, and according to critics: “An elegant and refined execution, both in tailoring and color, ideally matching the clair-obscure tones, were these Verdi partitur costumes by Marika Danč.”

Marika was still a student when she fashioned costumes for Ladarice, a folklore ensemble; uniforms for the Relay of Youth race in Zagreb; costumes for KUD “Ivan Goran Kovačić”, and the Zagreb Madrigalists. A special chapter in itself consists of her costume-scenographic design projects together with RTV Zagreb for a large number of dramatic, cultural, artistic and entertainment programs that included many legendary directors, like Anton Marti.

The atmosphere of gatherings, lunches, correspondence, working on various projects at the same time, conversations with fellow artists, theater personnel and architects pulled her into the epicenter and left her little space for anything other than creating and working.

Theater work is magical. It is a collective workshop for many arts and crafts with people co-creating a marvelous theatrical and living play, spending months of intense processes on it, to bring forth a holistic production of sound, movement, acting, emotion and aesthetics. They say the preview is always a miracle. Marika felt at home in this miraculous world and literally moved to the theater for individual projects, burying herself in 24 hours of labor.

Alongside her studies and intensive costume design, she busied herself with tapestry. Her unlimited creative urge and readiness to push herself, plus the years she spent as Jagoda Buić’s assistant, very quickly led her on a path of independent self-expression in a complex artistic discipline, where soft contours of (mostly) natural materials required a knowledge of drawing, painting, design, architecture, sculpting, scenography and illustration and, of course, a mastery of the techniques of dyeing and weaving.

In 1975 and again the following year, as part of the country’s purchasing of artworks for galleries, museums and other institutions and public places, two of Marika Danč’s tapestries were bought, one of which was hung in the Museum of Arts and Crafts in Zagreb, the other in Čakovec.

In the second half of the 1970s, Marika served as president of the textile section (tapestry, costume design, fashion) at the Croatian Association of Fine Artists of Applied Arts (ULUPUH), which brings together artists from all fields of visual and applied arts: set designers; graphics and industrial designers; restorers; ceramic, metal, glass and porcelain artists, and many others. Apart from diverse organizational and professional functions, it is especially committed to issues concerning studios for artists.

Marika remained in close contact with her native Lendava, particularly with her mother, brother and a few childhood friends, who, like herself, were already on study- and other courses of youth. Among those close to her were Lendava’s writer and journalist, Sándor Szúnyogh, and an especially important, vital connection with his colleague, Štefan Galič, later embracing both families until his untimely death. She also maintained contact with the married couple, Ferenc Király and Suzanne Király-Moss, that strengthened after Marika married.

After her husband’s death in 1965, Marika’s mother took a job at the INDIP factory, founded in 1904 by the Hungaria-Első Hazai Ernyőgyár umbrella factory. It experienced many ups and downs in those turbulent times, but began to improve in the early 1960s, thanks to modern business premises and approaches. The company expanded its activities to include knitting, changed its name to INDIP (Umbrella and Knitwear Industry), doubled its number of employees and exported its goods to Western European markets, the USA and Canada.

Between 1971 and 1976, Marika designed a great many sample products and collections for INDIP, with which the company presented itself at fashion trade shows in Ljubljana, Zagreb and Belgrade. From drafts and drawings that she keeps in folders, we see her development from more classical to freer sketches, especially in her exquisitely modern, stylistic and elegant patterns for fashionable pieces of knitwear. Before the days of low-cost products of Asian origin, quality materials were the norm, and textile apparel was made to be worn for decades. A youthful, modern and completely cosmopolitan style that successfully combines everyday usage and elegance, classical canons of aesthetics and modern trends, distinguishes Marika’s creations.

The 1970s were a period of high achievements in the former country, too. All types of art dealt successfully with modern movements, tapestry also belonging to a revived artistic discipline, embracing new, authentic dimensions that transitioned into the co-creation of interiors in a spatial, three-dimensional sense.

Marika’s endeavors are acknowledged throughout the country and internationally, placing her on the very Olympus of artistic tapestry design. She developed herself into an authentic artist, prominent in the context of profession, criteria and popularity.

An open and playful character is ideal for working in theatrical, film and television circles; it augments lively and fruitful exchanges of opinion and artistic debate, and above all, the possibility of working on many projects whose quality and importance keep pace with the times. Artists, performances, festivals and productions beyond different periods, styles and political systems acquire and maintain an iconic status. It was an interesting time with interesting people and their creativity, and Marika Danč was an organic part of it, professionally and privately.

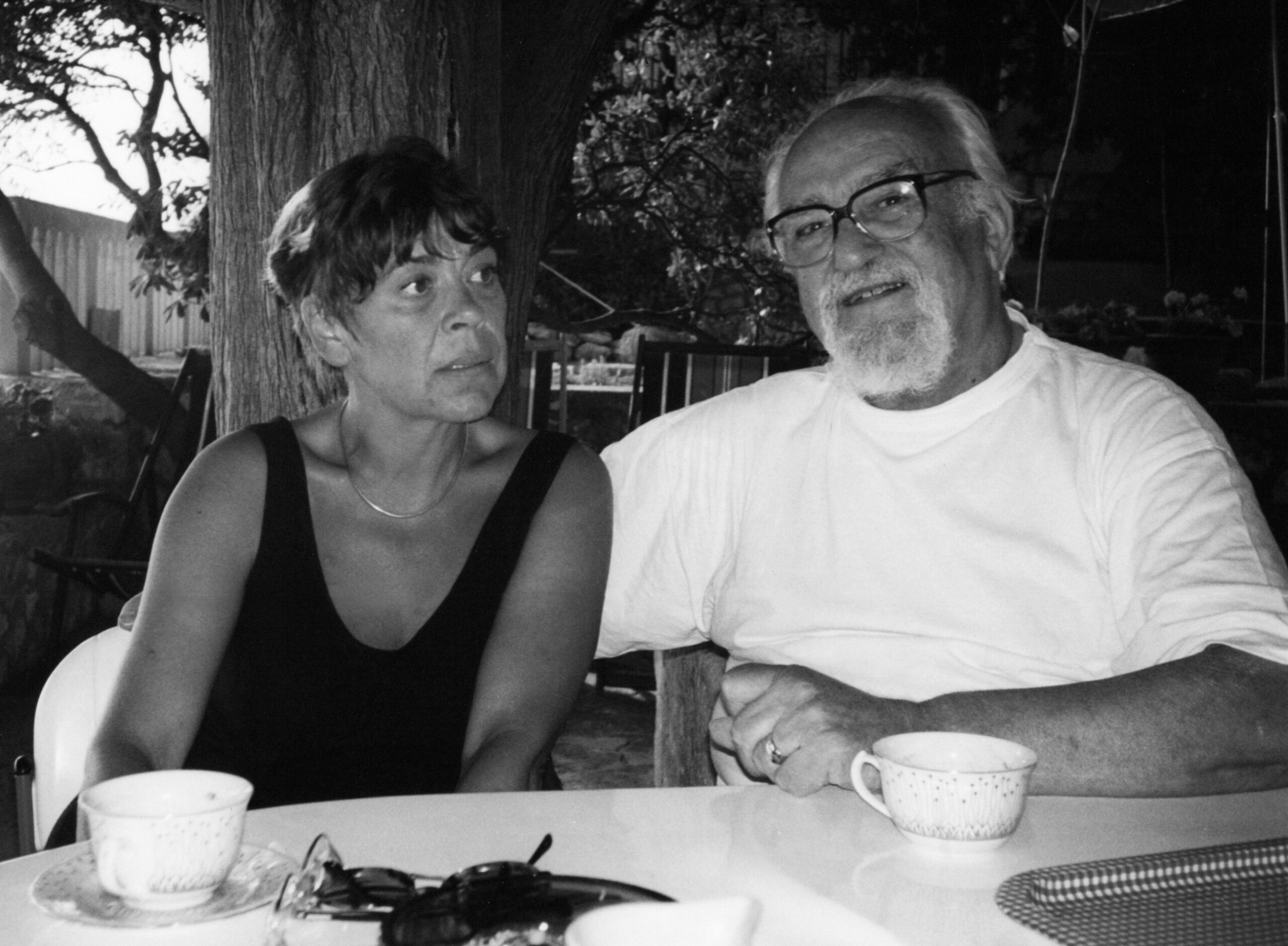

Toward the end of 1979 at a birthday party with friend, graphics and industrial designer and photographer, Željko Borčić, and his American wife, Marika met a friend of theirs from the USA, who was employed in Ljubljana but made private and business trips to Zagreb. At that point, Marika was inordinately occupied with several art projects and her position as assistant; she was also teaching, exhibiting, active with television, festivals, theaters, and she never saw herself in a dramatic love story that would deplete her energy. Tom Roth’s charming directness and gallant perseverance led to their marriage in June 1981. As Marika stated in several interviews, love brought her down to earth, but she never regretted it. At some point, every creative and hard-working woman faces a life-altering decision with far-reaching consequences. Some driving force dispelled Marika’s doubts; with a short move to Ljubljana and then a permanent one to Munich, she worked, created and exhibited with the same eagerness. But costume and scenographic design engagements were understandably rarer, and since they required teamwork and extended stays in other places, that was difficult to carry out in her new surroundings. This period includes her first participation on a film, Twilight Time, produced in 1982 by MGM United Artists, directed by Goran Paskaljavić and starring Karl Malden.

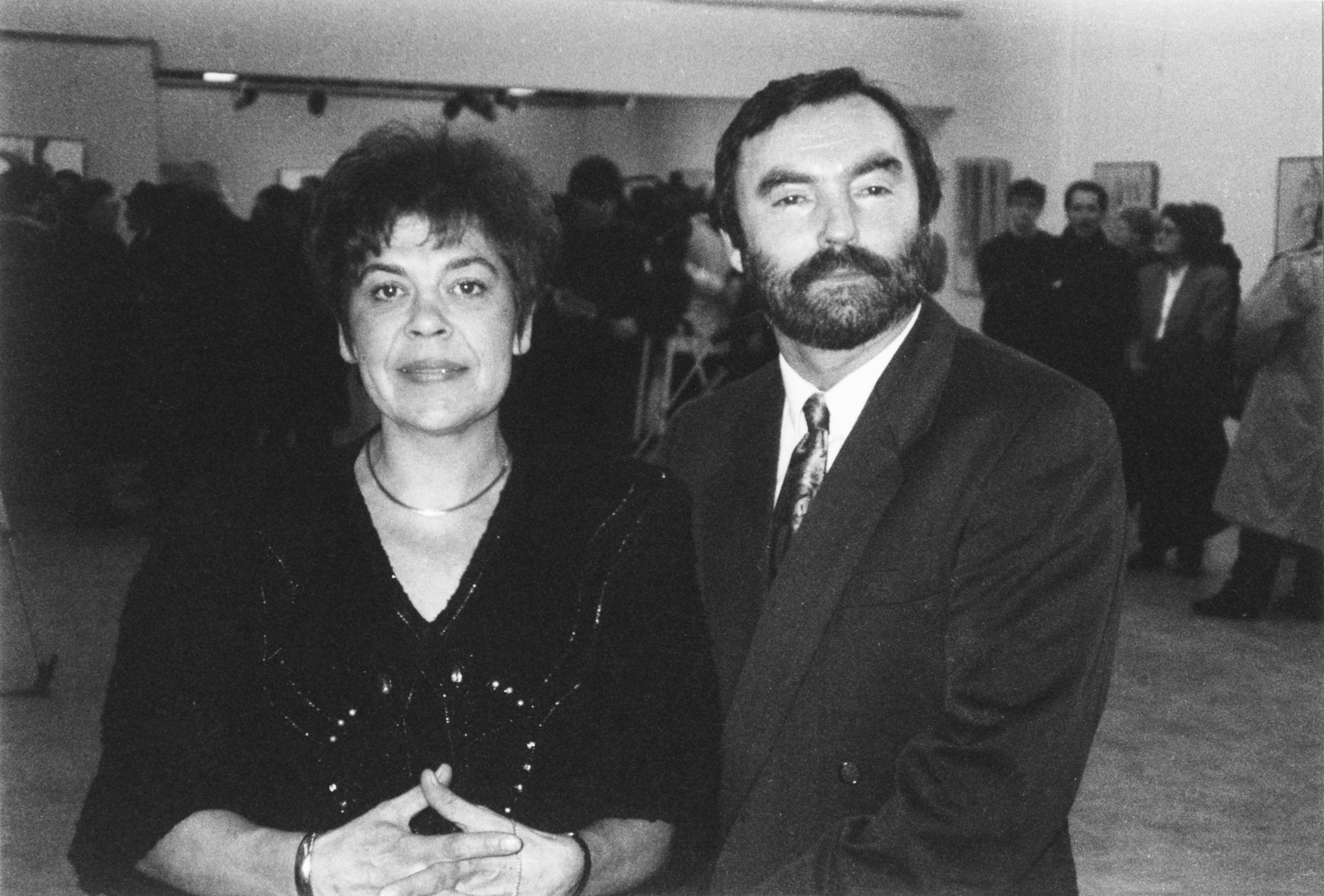

Marika’s three-year stay in Ljubljana allowed her to strengthen and expand contacts with Slovene colleagues; in the 1980s, she exhibited independently in Lendava, Ljubljana, Zagreb and Munich, participated in projects at Ljubljana’s Glej and Šentjakob theaters and in several domestic and international group exhibitions of tapestry. Ljubljana’s Mala Galerija in 1982, and Zagreb’s Karas Gallery in 1983 showed her most interesting tapestries. That same year, at the invitation of Zoran Kržišnik, she exhibited a series of works at the Club of Cultural and Scientific Workers in Ljubljana, initially only costume sketches, that – ever methodical and disciplined — she made by combining drawing and macramé. She completed a series of 28 paintings, as refined as filigree, exceptional visually and in their execution. She also had her first large art show in Lendava, which meant a lot to her. For all her outstanding success on a national level, Lendava remains an emotional constant in her heart.

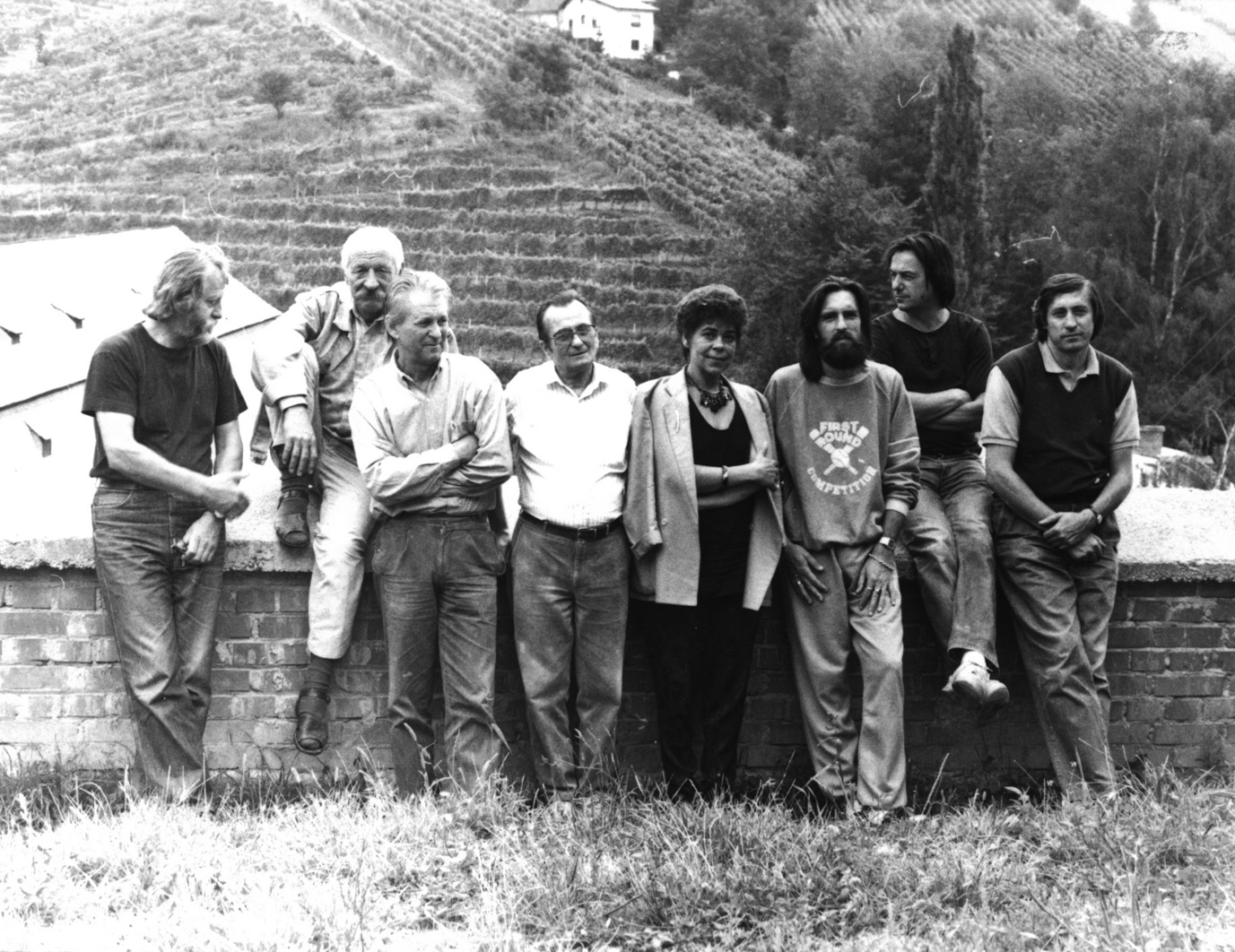

During her stay in Ljubljana, friendships with fellow residents and colleagues like Jože Ciuha, Tomaž Kržišnik, and art historian, Zoran Kržišnik, and their wives, deepened and eventually became life-long. Many wonderful memories remain from having shared fruitful creativity, exhibitions and socializing with them that continued even after she moved to Munich.

By this time, Marika had experienced ten years of abundant costume designing on 40 projects for theater, television dramas, films, and festival performances of opera and ballet that she counts among her favorites for the creative freedom they afforded – in both classically-sewn costumes and macramé, some of which received unprecedented responses even in untutored circles.

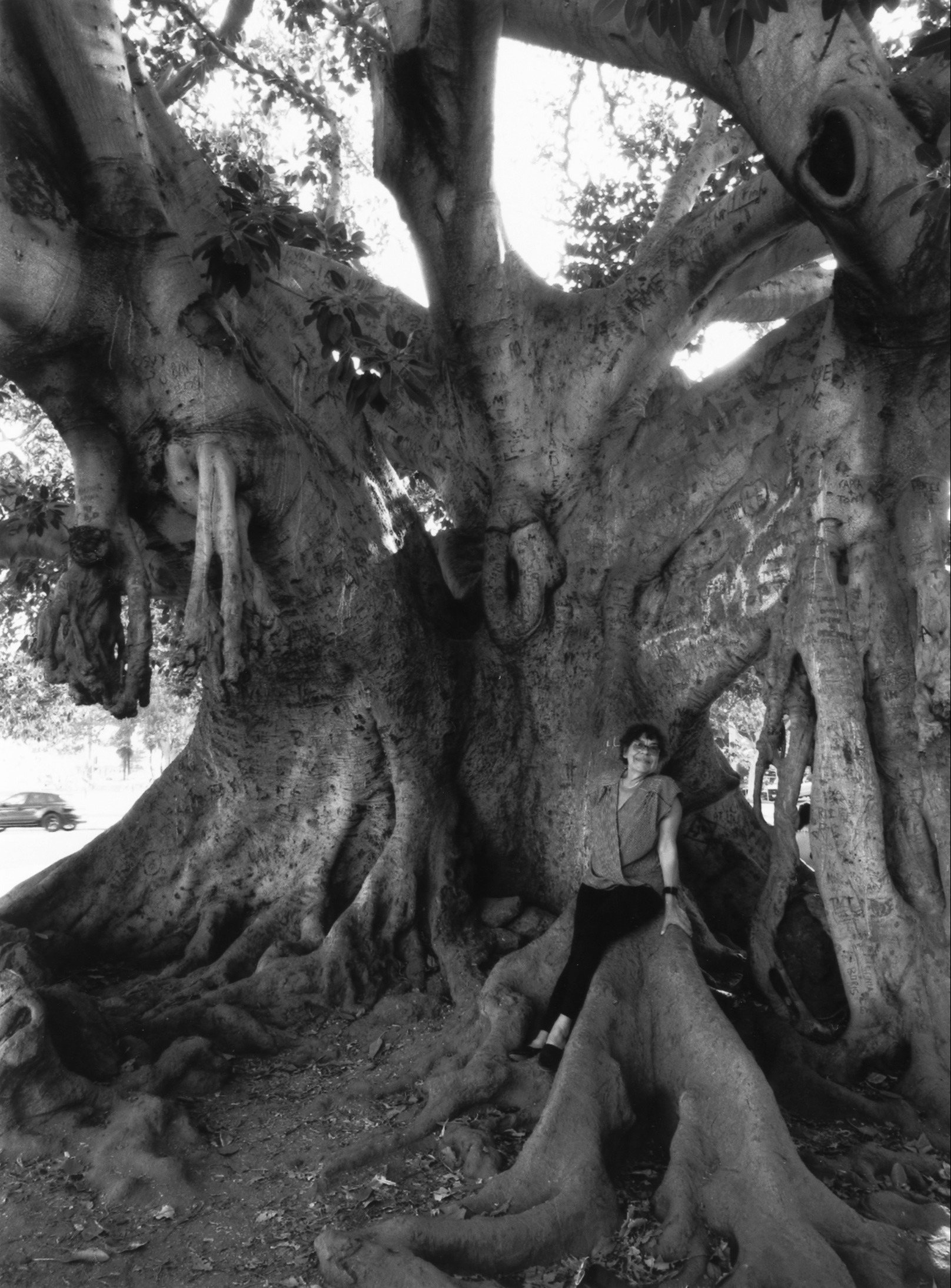

The move to Munich in 1983 marked an important turning point, completely changing Marika’s way of life. Wherever else she had lived, she had friends, colleagues, acquaintances, coworkers, extensive socializing, conversing and participating. The emptiness of the foreign city was therefore so much more traumatic and frustrating, but, as many times before, she solved the problem through art. Innumerable galleries and museums offered venues, and a wave of traveling around the world began for her, that, with studious preparations, were an unconditional source of inspiration, motivation and a vital impetus for creating and confirming her views on the magnificence of nature in its many variations, the untouched as well as the cultivated. Like everything else, Marika tackled her travels with consistency, taking hundreds of photographs of the natural world. She was mostly impressed by Japan, fascinated at every turn. The ginkgo tree was special in both its visual and mythological symbolism, and its incredible endurance — the only living being able to survive the consequences of nuclear explosion. Trees remained her main focus, in her world of art as well as in her everyday experiences.

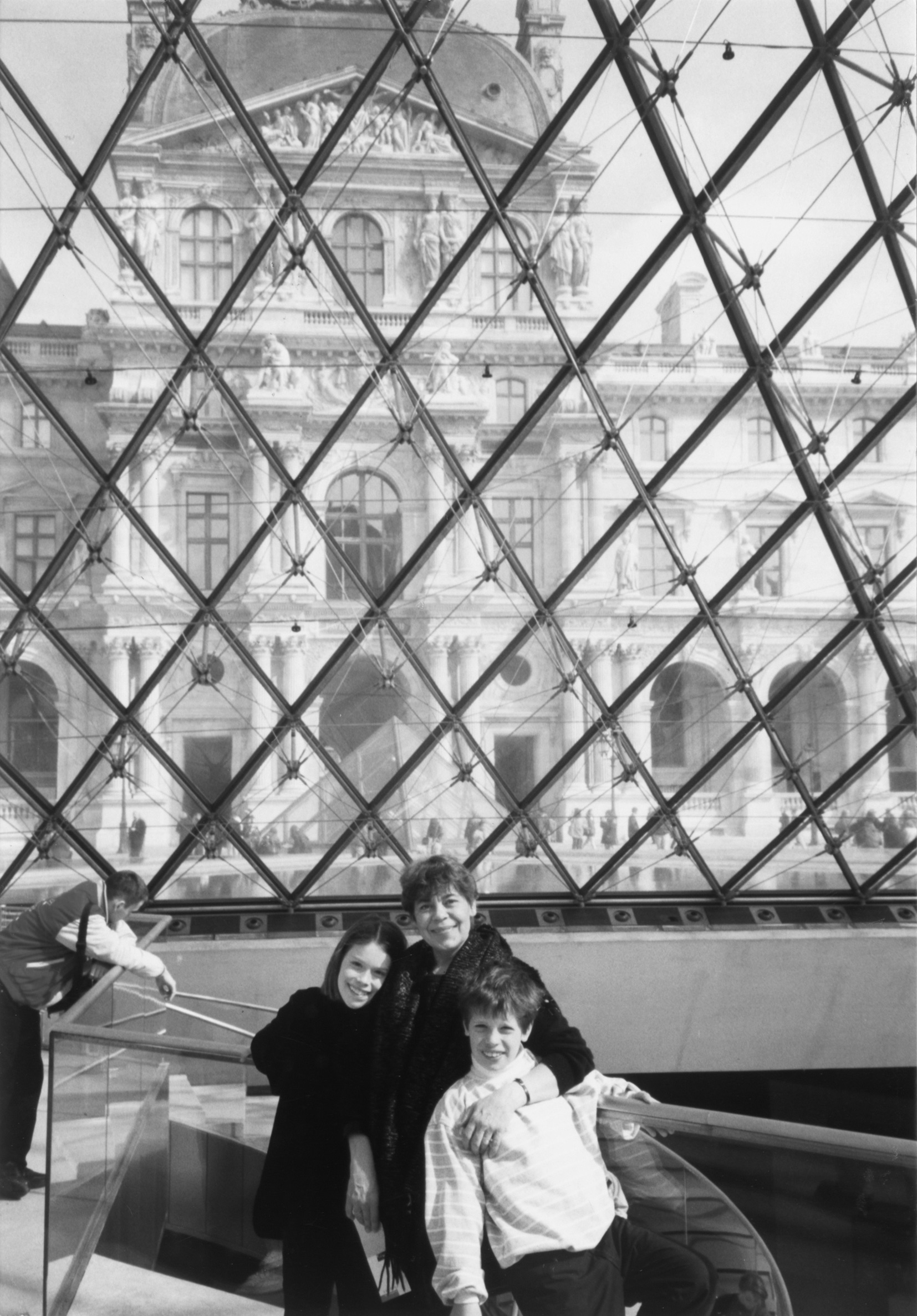

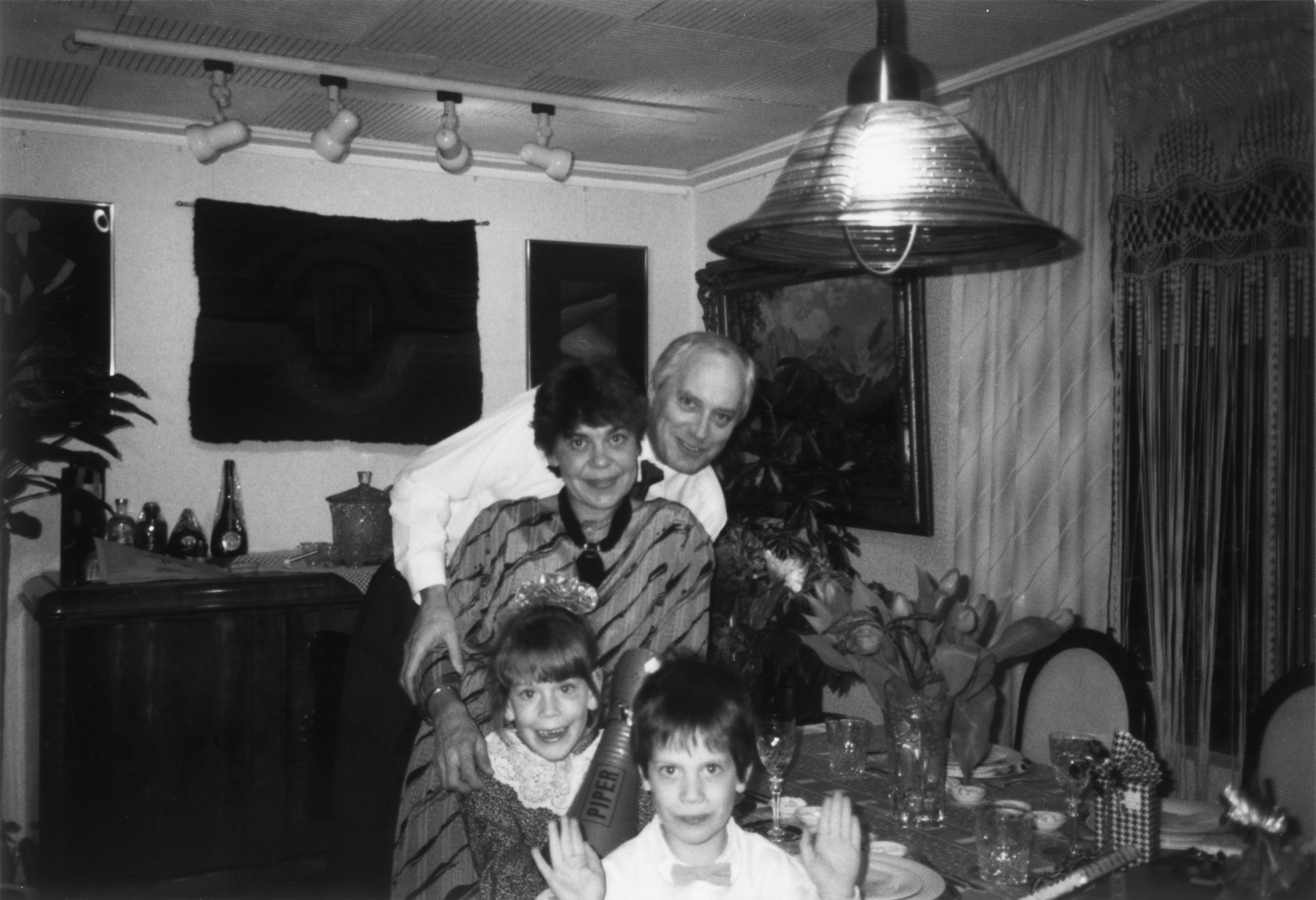

Events of even more significance added to Marika’s open craving to learn the ways of the world — the birth of her daughter Sarah in 1986, and son Andy in 1987. All superlatives about her creativity, enthusiasm, bravura performances and dedication gained momentum with this new project, another role she could devote herself to with all her characteristic commitment. She describes them as her most important and best works of art, and they filled and replaced everything she had left behind. Her career became less intensive. Nonetheless, she dealt with projects and fresh creative directions in the 90s, and even alongside growing children, exhibited and sold her works successfully in Munich, Ljubljana, Piran, Bled, Novo Mesto and back home. In 1995, she held a large, retrospective exhibition in the Murska Sobota Gallery and another in Lendava’s Hotel Elizabeta, that was becoming an interesting exhibition hall. She displayed tapestries in Italy, the USA, Slovenia, Hungary and Croatia as unreservedly as in previous decades, but constantly returned to her home town’s international fine art colonies and the group exhibitions of Lendava and Pomurje artists. Confirmation of Marika Danč-Roth’s brilliant creative oeuvre is her inclusion in the Encyclopedia of Croatian Art (the Miroslav Krleža Lexicographic Institute, Zagreb 1995).

A fundamental shift occured at this time in Marika’s method of expression, a changeover from tapestry to the combined technique of drawing and textile relief in macramé. Many trips to Hawaii in 1992 acquainted her with the banyan tree, captivating her, and in many ways it defined the essence of her creative configuration. Capturing her attention later, too, in many Asian countries and areas in the USA (Florida, Los Angeles, New Orleans), the banyan tree began to dominate her artistic themes, carrying a many-layered symbolism. That special tree, whose aerial roots grow from top to bottom and form stunning visual arrangements, completely enchanted Marika, sending her on a new journey of expression, where she combined her two primary loves: drawing and working with natural threads made of silk and cotton, gold or silver. The embossed roots stand out from a two-dimensional surface and luxuriate beyond the frame of a given format, reflecting the true nature of the tree that inspired her so much.

Life’s timeline and creative aims also bring pitfalls and gaps. Tectonic changes submerged the ground beneath Marika’s feet, empty spaces and chasms appeared, but her inexhaustible love of life overcame them with fervor and perseverance. And, as so often happened in the past, when lost and disappointed, she found refuge and consolation in trees, nature, and art. This time her ever-present pencil and sketchbook were decisively therapeutic, and most of all, so were the trees. The fascination with this motif that had filled Marika’s life now gained a special charge. As she observed the forest and trees on her walks, she perceived a message of survival, hope, courage. On small formats she created an extraordinary series of sensitive statements in pencil on paper, accumulating more than 3,000 of them over the years.

It was not only in those intimate artistic testimonies that she returned to her original love – pencil drawings. She also did so occupationally, with brilliance and skill. Portraits joined her abiding tree theme, and along with pedagogical obligations for many courses and seminars, she painted more than 100 people in the first decade of the 21st century.

When her family and life in general underwent its significant change in the year 2000, and for the next decade and a half, Marika devoted herself to pedagogy by teaching at the Volkshochschule in Munich (from 2001), and to theatrical and film projects. The Volkshochschule is a more diversified and complex version of our [t/n: Slovenian] folk universities. Marika taught decorating and design techniques and other types of creative expression. The most popular courses were beginner and advanced drawing, thematic drawing of natural forms, roots and trees, and floral motifs in watercolor techniques; fashion and figure drawing, portrait and torso drawing. She also frequently conducted courses in the practical knowledge of picture framing, matting, and arranging paintings or photographs for exhibitions. She prepared many students for studies or entrance exams at art schools and academies, following and mentoring several of them for years, sometimes as many as ten. Among her more engaging projects were collaboration on a performance of The Three Musketeers, with Orlando Bloom and Milla Jovovich in leading roles, and on the film, King Ludwig II.

In 2009, at the initiative and invitation of colleague and Munich costume designer, Karola von Klier, Marika began a long-standing association on a project in the town of Oberammergau, famous for its Passion Play. Considered an important cultural event in Germany, it is performed once in a decade, a custom dating back to mid-1634, when many people died of the plague during the Thirty Year War, and the townspeople vowed to stage the Passion of Jesus every ten years if God put an end to the epidemic. Tradition has it that nobody died of the plague after that vow.

During the ten-year interval of the world-famous Oberammergau Passion, smaller productions with predominantly biblical content are presented on Europe’s largest open-air stage.

The impressive visual presentation of this enormous theatrical project, its organization and execution, has always attracted large audiences from all over the world (half a million visitors in the last few decades), among them the most eminent guests of the times: presidents of countries and governments, crowned heads and bishops, cardinals and future popes, composers and artists like Richard Wagner, Richard Strauss, Rabindranath Tagore, Franz Liszt, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone Beauvoir…

Performances and artistic approaches changed over the centuries, and 1990 was considered a year of generational crossroads and artistic reform. Christian Stückl took over the concept and directing of the performance, and together with costume designer Stefan Hagenauer, they created an updated version. Only Oberammergau locals were allowed to perform on stage, and in the year 2000 they already numbered more than 2,500. The 100-member orchestra, choir and a large technical and performance team needed more than six months for preparation. In 2009, Marika Danč-Roth, who was a part of the costume design team, was put in charge of managing costumes, which meant up to 4,500 different pieces for a show. Marika was in a group of over 20 seamstresses and a large operational staff that numbered hundreds of members and in the process of preparing and producing costumes, measurments and adjustments, her consistency, accuracy and knowledge of materials, their properties, the chemicals needed for aging, soiling or reuse, came to the fore. Her exceptional knowhow concerning materials and the chemical processes of patinating, bleaching, polishing, impregnation, glazing, laminating, coloring and sandblasting proved once again that Marika was an indispensable and important part of the production. She participated in the project until she retired and moved to Lendava in 2015.

From the start, Marika Danč-Roth went her own way, hurdling national, small and large city borders and restrictions with ease. She was fully and confidently involved in the time and space of the former Yugoslavia in the second half of the 20th century, and later in Slovenia, Croatia and Germany. Her character and talent opened doors to significant worlds, where she was considered a popular colleague, a reliable co-worker and a fabulous creator, with many talents and much knowledge. Her works are in private collections in the USA, Germany, Slovenia, Japan and Croatia.

Exhibitions and personal relations always kept her bound to Lendava, and it remains her mental, emotional and creative living space. Upon her return, her thoughts were focused on a quiet retirement and leisurely creativity, but concrete obligations to house and garden overshadowed her plan. However, she remains involved in artistic events — from instructive activities at the LindArt colony, group exhibitions and art colonies to organizing extensive photo-documentations, material, books, and works of art.

Marika’s daughter, Sarah, lives in Los Angeles, her son, Andy, in Munich. Strong, close emotional ties connect them, relieving Marika’s sense of emptiness; modern telecommunication options help a great deal. Both daughter and son have mild, cultured and humane characters, and that is just one more, and the crowning, proof of how Marika has dealt with everything in her life in a superb and enviably flawless manner.